Guest Column | Don't Kill Our Robot Overlords... Yet - Part 2

Now You See It, Now You’re Screwed

This article is Part 2 of a (for now) two-part series about AI: what it is, what it isn’t, and how our very human ways of seeing shape what we think we’re dealing with. In case you missed Part 1, read it here:

Now You See It

In film school, one of the first lessons I learned was about perception. There’s a famous early experiment called the Kuleshov Effect involving moving pictures: People were shown two sequential images. The second image always stayed the same—a person’s face with a neutral expression. But the first image changed. If it was a bowl of soup, people interpreted the person as hungry. If it was a child’s coffin, they thought he was grieving. Same image. Different meaning. Context created narrative.

That experiment wrecked my ability to watch TV without feeling manipulated—until streaming came along and bingeing five episodes in a row made me feel like I had the upper hand again. Take that, White Lotus.

Now You’re Screwed

What’s most unnerving about AI isn’t what it produces—it’s what we believe its output reveals. Just like the Kuleshov Effect taught us that context changes everything, we approach AI with our own preloaded footage: fear, awe, TED Talks, loss of our dignity, and the amalgamation of every piece of dystopian fiction in human history.

So when AI hacks up a poem about a capybara on a bicycle, we don’t just laugh—we wonder if it’s sentient. We read meaning into a blank face because we want it to mean something. And as humans we are naturally voyeurs. It’s easy to see something and decide it matters, because we looked at it.

And in that act of watching—of framing what we see—we reveal just as much about ourselves as we do about AI.

The question isn’t just “What is this?”

It’s “Why did I see it that way?”

Choosing the Frame

The good news is: we can choose the frame. Or at the very least, if we pause, we can notice the lens we’re using. That moment of reflection? That’s critical thinking in action. It’s what separates healthy curiosity from spiraling paranoia.

Not everything means everything. And not everything is worth our attention.

Is This AI? (Yes.)

The idea that soon—very soon—we won’t be able to tell if something was made by AI or by a human is now a cliché. And it’s also the wrong question.

If AI is woven into everything digital, and if it draws from the entire internet—a place we built together, but over a very short span in the history of humans—then the real question is: Does it matter?

Did it make you feel something? Did it affect your decisions, your loved ones, your rights? If yes—dig in. If no—move on. It’s okay to shelf it like a book you’ll never check out.

When to Care

In a post-AI world, it’s okay in many cases to not give any f**ks whether something was made by AI or a human. That TikTok your cousin shared? Zero f**ks. The executive order the plutocrat cos-playing POTUS deployed with five minutes to close on a Friday? PAY THE F**K ATTENTION AND ACTIVATE BRAIN MODE, IMMEDIATELY.

The capybara poem you wrote that your friends thought was, “Like, whoah-dude, 😂”? At least one fuck—because the humor is in the fact that an AI wrote it... but it’s fleeting because as AI gets better, the capybara poem becomes the Ally McBeal dancing baby (yes we are old if we get the reference) of whatever year this is and looks more like something your eight-year-old yakked up during the four seconds you allowed them to play Robolx.

Three Questions to Ask Yourself

We need to start asking:

Is this AI?This could be AI (this is no longer a question)Does it matter if it is?

Do I need to act on it (read: check the source or credibility)?

In a world where anything could be AI-generative, if you don’t ask these questions you:

Think everything is AI (and spiral into a wacko conspiracy nut), or

Care about nothing (and become the manipulated)

Either way, someone else wins. There’s no binge-and-move-on. No privileged white tourists confined by the frames of their prestige dramady.

This isn’t White Lotus, it’s real-life media literacy.

That means you have to be the frame. Not the algorithm. What you choose to notice, question, and follow up on matters more than ever. Critical thinking isn’t just protection against manipulation—it’s what makes you a participant in this moment, not just an observer.

Final Frame

If words are metaphors for shared understanding, then AI is just the next natural metaphor in our collective lexicon. It’s not here to smite us. It’s here because it is us. And we keep making it. So keep writing. Keep creating. Keep being human.

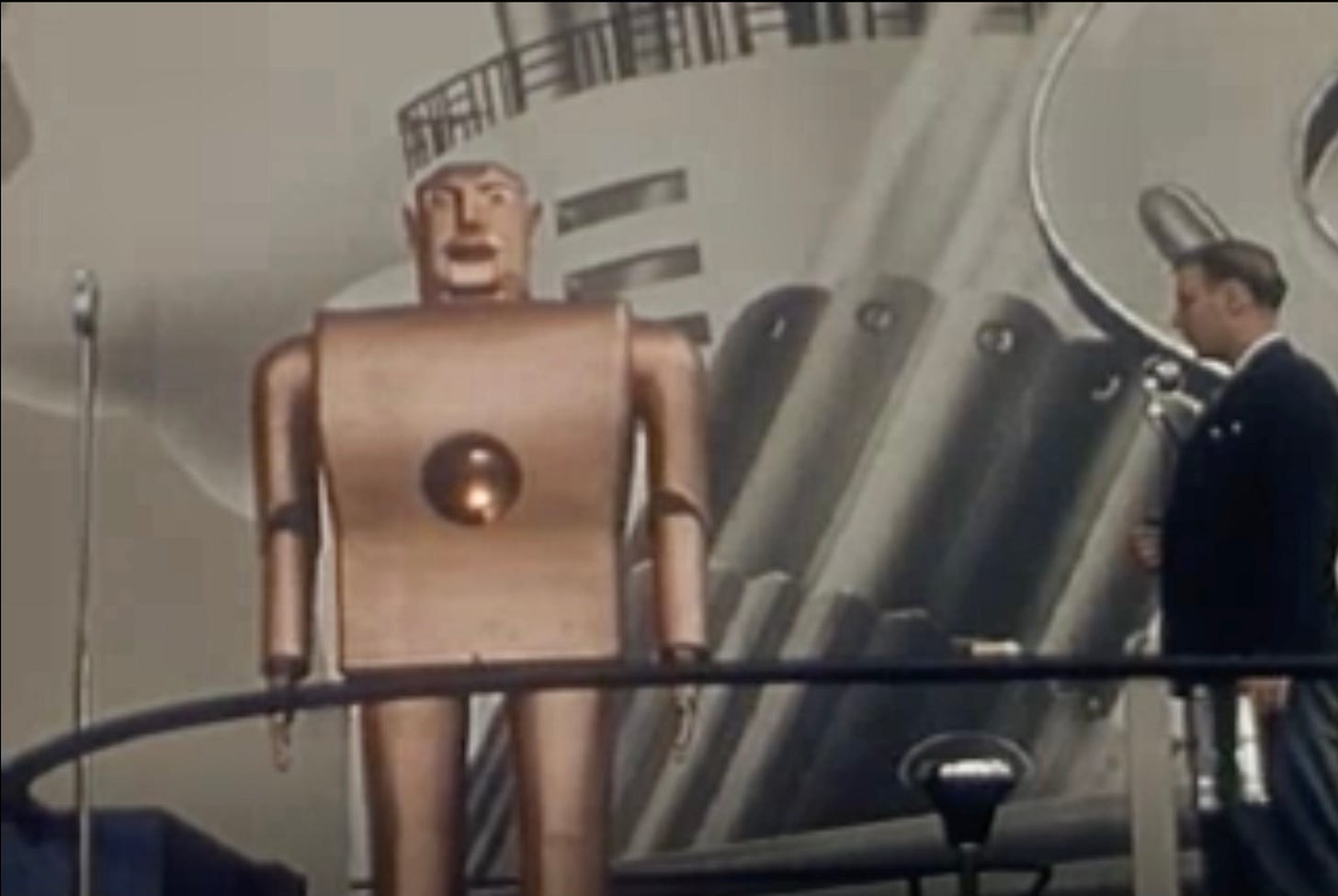

We built the robots.

We taught them what to see.

And now it’s up to us to decide what any of it means.

Capybara rides

Too small helmet, big ambition—

Honk if AI wrote.

Many thanks to my mom, the maddest mother I know, for letting me guest on her Substack. Your wisdom and guidance—and the fact that you were my AP English teacher for the better part of my high school years—shaped not just my writing voice, but my actual voice—the one that asks questions, pushes back, and thrives in the collective consciousness of humanity

If you’re interested in the history of AI, here is a brief timeline as generated by GPT-4o with the prompt:

What was the first ai generated content?

The answer depends on how you define “AI” and what you mean by “generated content”—but here’s a brief timeline of milestones that could each be considered a form of “first” AI-generated content:

🧮 1950s–60s: The Very Firsts (Rule-Based Systems)

🖨️ 1956 — The Logic Theorist

Developed by Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon, this program proved mathematical theorems. While not “creative,” it was arguably the first AI to generate output that mimicked human reasoning.

📜 1961 — First AI-generated poem (sort of)

IBM’s Mark II computer was used by Theo Lutz to generate stochastic poetry using a vocabulary and grammar rules. It randomly assembled phrases like “the strong machine dreams” using logic and probability.

💬 1966 — ELIZA (first conversational AI)

Created by Joseph Weizenbaum, ELIZA simulated a Rogerian therapist by mirroring a user’s statements. While not generative in the way ChatGPT is, it was the first widely known system to produce seemingly human-like text responses.

🎵 1970s — First AI-generated music

David Cope’s early experiments and others around that time used rule-based systems to create simple compositions. Cope later developed EMI (Experiments in Musical Intelligence), which could generate music in the style of classical composers.

🧠 2014 — GANs: The true beginning of AI-generated content as we know it

When Ian Goodfellow introduced Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), AI could begin generating novel images, art, and deepfakes. This is what unlocked the era of AI-generated faces, paintings, and video.

🤖 2015–2020s — The explosion

OpenAI’s GPT-2 (2019): One of the first natural language models to create surprisingly coherent text.

DALL·E, Midjourney, etc. (2021+): AI-generated visual art hits the mainstream.

Runway, Synthesia, etc.: Video, voice, and even virtual actors are now AI-generated.

🧠 TL;DR:

| 1961 | Text | First AI-generated poetry (Theo Lutz)

| 1966 | Chat | *ELIZA*: first chatbot to simulate conversation

| 1970s | Music | Early AI-generated music compositions (e.g. David Cope)

| 2014 | Visual | GANs enable true AI image generation (Ian Goodfellow)

| 2019+ | Scalable | GPT, DALL·E, and widespread generative AI content

.